Holywell Bay unsurprisingly gets its name from a Holy Well, but there are 2 rival contenders for this! The first is in the valley at Trevarrick (near the 18th hole of Holywell Golf Course). The second, and more likely the original, is a freshwater spring in a sea cave at the north end of the beach. In Cornish, the name is Porth Elyn, meaning "cove of the clear stream" which also lends weight to the latter being the original Holy Well.

The location of the cave is not that obvious unless you know where to look. If you follow the cliffs out towards the headland, you eventually pass a rocky ridge protruding parallel to the headland. Behind this is an area of boulders, and behind the boulders is the cave. Depending on the movement of the sand in rough seas, you may need to climb over boulders or wade through a rockpool to reach the cave.

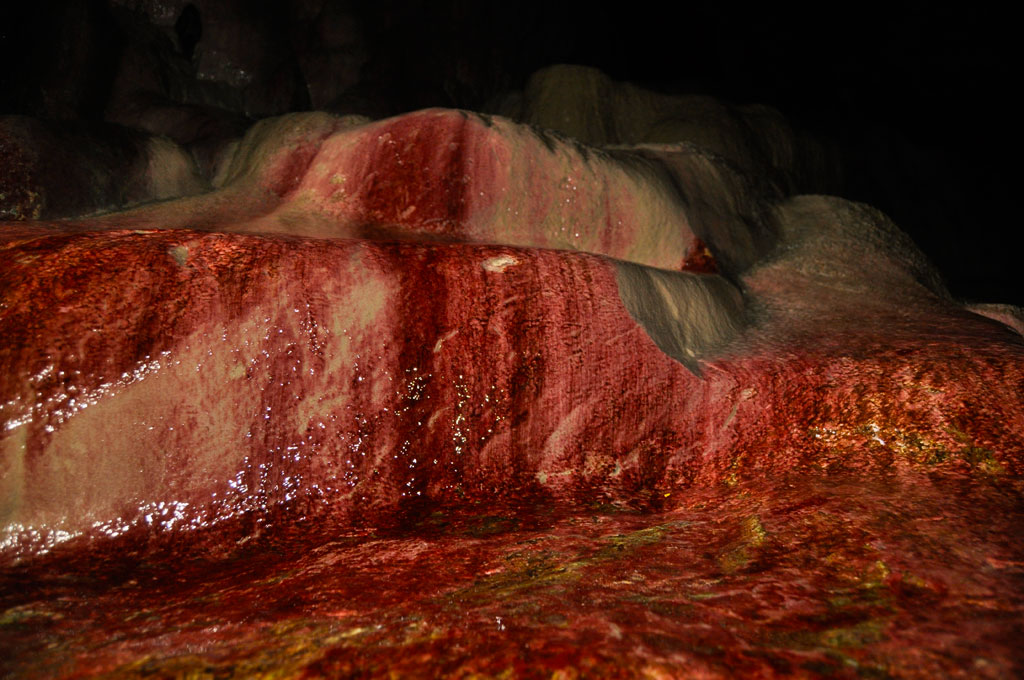

Calcium carbonate dissolved in the springwater has created a spectacular series of natural basins fed by the well. The source of the calcium carbonate was originally thought to be the fragments of shell in the sand dunes, as there are few sedimentary rocks in this part of Cornwall. However, there are a few thin bands of limestone in this area and current thinking is that the source of the well may be one of these, but it is not known for certain.

If sedimentary rocks containing calcium carbonate are pretty scarce, you may be wondering where the shellfish themselves got their calcium carbonate from. Sea water contains a range of dissolved salts, not just the sodium chloride that you can taste. Around 1% of the dissolved material is in fact calcium. Molluscs are able to extract the calcium ions from the seawater to construct their shells.

A significant proportion of the sand on North Cornish beaches is fragments of seashell which gives it its golden colour. For centuries, the sand has been used to lime the acidic moorland soils and elaborate schemes such as the Bude Canal and Bodmin-Wenford Railway (now the Camel Trail) were devised to transport the valuable sand inland.

It's also not hard to imagine that the blood-red algae growing in the springwater may have caused more than a little excitement amongst the superstitious Pagan people.

In the interests of medical science, we unplugged a teenager from its X-Box and exposed it to some sunlight and some water from the Holy Well. Ascent to the well was deemed "a bit sketchy", the well itself earned a surprised "well cool" and the red algae "looks like gore". The conclusion of our experiment is, despite a resemblance to vampires, teenagers do not burst into flames or explode into a pool of red gloop (despite the picture below) when exposed to sunlight or Holy Water. However, the healing properties of the Holy Water don't seem to extend to curing X-Box addiction.

Cornwall's Cotton Castle

In Turkey, Pamukkale (Turkish for "Cotton Castle") is a huge tourist attraction, however Cornwall's equivalent is more of a hidden gem. The spring in the cave is along the side of Kelsey Head and is only accessible at the lowest part of the tide (i.e. when you can see the shipwreck protruding from the waves). |

| Shipwreck at Holywell Bay at low tide |

The location of the cave is not that obvious unless you know where to look. If you follow the cliffs out towards the headland, you eventually pass a rocky ridge protruding parallel to the headland. Behind this is an area of boulders, and behind the boulders is the cave. Depending on the movement of the sand in rough seas, you may need to climb over boulders or wade through a rockpool to reach the cave.

Calcium carbonate dissolved in the springwater has created a spectacular series of natural basins fed by the well. The source of the calcium carbonate was originally thought to be the fragments of shell in the sand dunes, as there are few sedimentary rocks in this part of Cornwall. However, there are a few thin bands of limestone in this area and current thinking is that the source of the well may be one of these, but it is not known for certain.

|

| The Holy Well |

A significant proportion of the sand on North Cornish beaches is fragments of seashell which gives it its golden colour. For centuries, the sand has been used to lime the acidic moorland soils and elaborate schemes such as the Bude Canal and Bodmin-Wenford Railway (now the Camel Trail) were devised to transport the valuable sand inland.

Walks that you can combine with a visit to the Holy Well

If you fancy visiting the well as part of a walk, we've written directions for a couple of walks from Holywell Bay which are available on our website, or you can download them as apps for your smartphone or tablet.

Sacred springs

Before Christianity, the Pagan Celtic people of Cornwall worshipped wonders of the natural world. Where clean, drinkable water welled up from the ground in a spring, this was seen as pretty awesome. Where the springwater dissolved minerals, for specific conditions (e.g. deficiency in a mineral) or where the water was antibacterial, the water appeared to have healing properties. The sites were seen as portals to another world, and is why fairies are often associated with springs.It's also not hard to imagine that the blood-red algae growing in the springwater may have caused more than a little excitement amongst the superstitious Pagan people.

In the interests of medical science, we unplugged a teenager from its X-Box and exposed it to some sunlight and some water from the Holy Well. Ascent to the well was deemed "a bit sketchy", the well itself earned a surprised "well cool" and the red algae "looks like gore". The conclusion of our experiment is, despite a resemblance to vampires, teenagers do not burst into flames or explode into a pool of red gloop (despite the picture below) when exposed to sunlight or Holy Water. However, the healing properties of the Holy Water don't seem to extend to curing X-Box addiction.

|

| No teenagers were harmed in the making of this blog post |